For many music scholars in the English-speaking world the writings of Donald Francis Tovey (1875–1940) remain a source of inspiration and insight. Tovey has something of interest to say about the majority of the most prominent composers in the tonal tradition, and his knack for finding metaphors to characterize salient musical events is widely acknowledged and celebrated. Though Tovey died over eighty years ago he remains, at some level, an intellectual presence in modern musicology, not least through later influential publications that have elaborated some of his ideas: Charles Rosen’s elucidation of the ‘classical style’, Joseph Kerman’s writings on the Beethoven string quartets, and James Webster’s analyses of sonata form in the music of Schubert and Brahms, to name but three. The term ‘purple patch’ as a means of describing chromatic passages within an otherwise stable diatonic context has become common parlance. Tovey’s critiques of textbook definitions, academic orthodoxies, and the ‘jelly-mould’ approach to musical form might still serve as useful provocations.

That Tovey is understood today predominantly as a music analyst is of course a testament to his achievements as a writer about music, but it also serves to construe his career in terms rather narrower than he himself might have recognized. The activity of analyzing music was clearly integral to Tovey’s existence: leafing through his personal scores that survive in the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Research Collections one senses that he was constitutionally unable to play, hear, or look at a piece of music without scribbling a few remarks about its aesthetic effect or the method of its construction. But Tovey was many other things as well as an analyst—a composer, a university professor, a conductor, and a highly regarded pianist who collaborated with leading musicians such as Joseph Joachim, Fritz and Adolf Busch, and Pablo Casals.

Tovey at his desk, photograph by Frederick Hollyer (ca 1900)

University of Edinburgh Centre for Research Collections, CLX-A-359 (E.2001.37)

The reception of Tovey’s thought about music has been shaped in particular by the publication of his popular Essays in Musical Analysis by Oxford University Press in the late 1930s. Although the essays are most commonly read today in a university context, as has often been noted, their original function was to accompany concerts—and normally ones that featured Tovey himself as a performer. In these texts Tovey sought to guide an interested audience through familiar and new compositions and, as is clear from the work of Catherine Dale, Tovey’s essays can helpfully be situated in the tradition of analytical programme notes that became popular in Britain during the second half of the nineteenth century. Rather than being aimed at scholars, such writings contributed to the trend of what Christian Thorau has recently theorized as ‘touristic listening’—whereby audiences were led through a given work by an accompanying programme note that provided a sense of what ‘ought’ to be heard. While it was in writing about Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms that Tovey contributed his most penetrating insights, the canon of works represented in these volumes is broader and more idiosyncratic than one might casually assume. Alongside such classics as Tovey’s analyses of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Haydn’s Creation, and Brahms’s symphonies are essays on music by Weelkes, Wilbye and Palestrina, Sibelius, Röntgen, and Respighi, together with many of Tovey’s British contemporaries (Elgar, Holst, Smyth, and Vaughan Williams).

Despite the value of the Essays in Musical Analysis many of Tovey’s most significant scholarly contributions are to be found elsewhere, especially in texts gathered in the posthumous volume Essays and Lectures on Music. This includes his surveys of the chamber music of Haydn and Brahms, the essay on tonality in Schubert, and an article on Beethoven’s approach to musical form. Other notable publications are the analytical companion to the Art of Fugue and Tovey’s edition of this work (which contains his own hypothetical conclusion to Bach’s contrapuntal masterpiece), his précis of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, and an unfinished monograph on Beethoven that was issued in its fragmentary form by Oxford University Press in 1944. Tovey’s introductory notes for the individual preludes and fugues of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier appeared in an edition of the work published by the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music and were aimed first and foremost at performers, though they also contain a healthy seasoning of analytical observation. These short essays might be viewed as representative of the entanglement of Tovey’s varied musical interests: to be found here are aesthetic evaluations, source criticism, observations on historical keyboard instruments, and thoughts about Bach’s compositional technique.

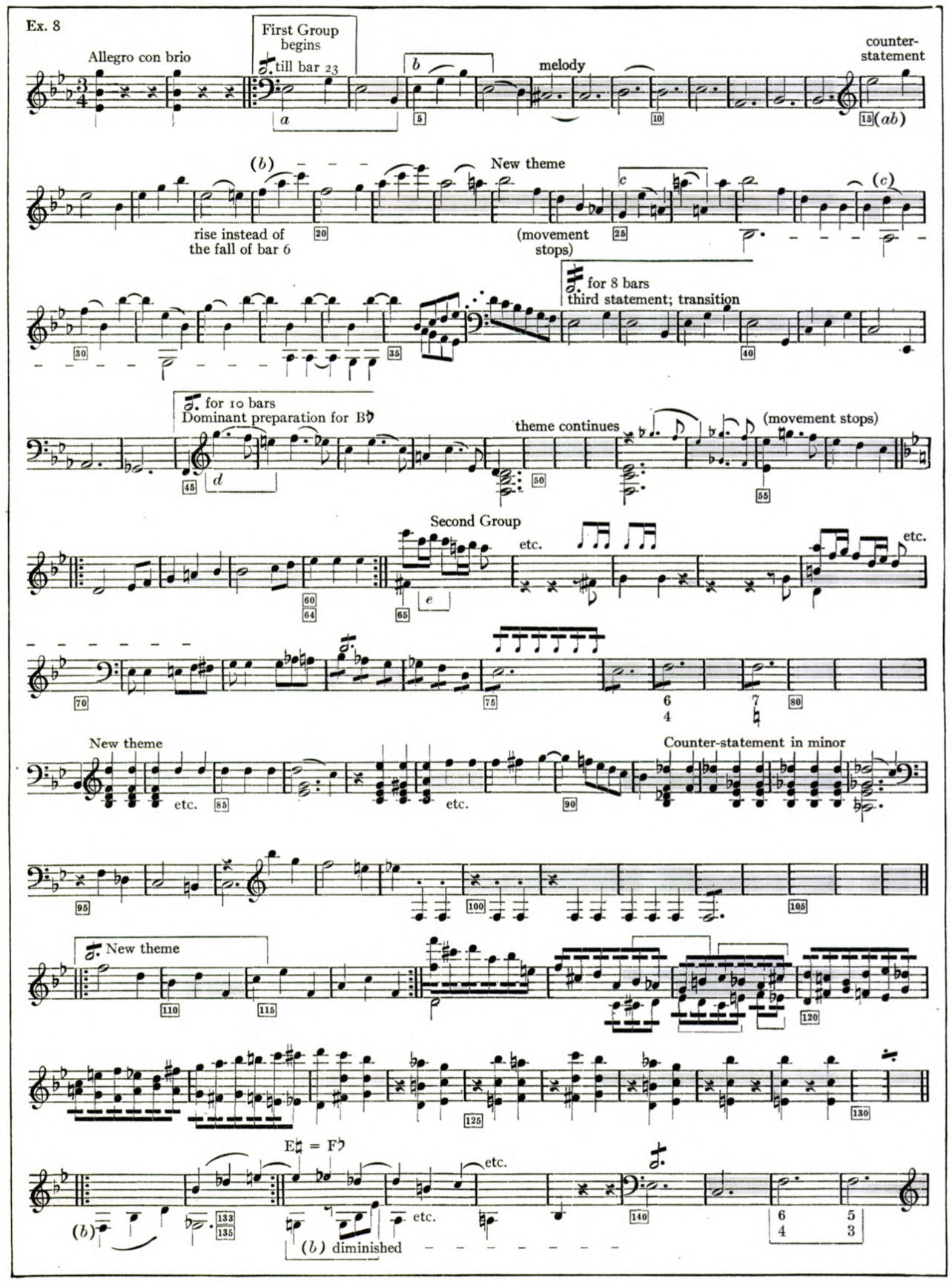

While Tovey is celebrated as one of the finest English-language writers about music it is worth noting that his gifts extended beyond being a prose stylist. In his companion to the Art of Fugue Tovey made good use of a system of symbols for fugal analysis that he adopted from Samuel Wesley and Charles Frederick Horn. To his frustration, the entries that Tovey contributed on musical subjects for the eleventh edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica appeared without musical examples. One of his planned, written out examples from Haydn’s Op. 9 quartets survives among his papers in Edinburgh and carries a characteristically acerbic annotation: ‘Intended for the Encyclopedia, but they won’t take musical illustrations; a pity, if you consider their treatment of Agriculture with full page photographs of prize sheep’. With the revised entries for the fourteenth edition Tovey had better luck and drew on a range of visually striking diagrams and concise musical illustrations. These are brilliantly chosen and exemplary for their communicative power. As observed by Scott Burnham, of particular note is the analytical reduction of the first movement of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony in Tovey’s entry on ‘sonata forms’. This gives a sense of the key events of the movement on a single musical staff (see example).

Extract from Tovey’s analytical reduction of the first movement of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony,

‘Sonata Forms’, Encyclopedia Britannica, 14th edition, vol. 20, 1929 p. 982.

Tovey might be felt as an awkward presence in the modern institutionalized world of music analysis and will no doubt puzzle some scholars through his bluster and seeming lack of interest in laying out new theoretical systems. There is nevertheless something instructive in Tovey’s example, both in terms of the depth of his knowledge about a treasured body musical works, and in his commitment to the idea that an interest in analytical engagement with music might be of fascination to a community of music lovers that extends beyond professional analysts.

Dr Reuben Phillips

British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow

Faculty of Music, University of Oxford

Tovey’s Writings

A Companion to ‘The Art of Fugue’ (London, 1931)

A Companion to Beethoven’s Pianoforte Sonatas (London, 1931)

Essays in Musical Analysis, 6 vols. (London, 1935–9)

Essays in Musical Analysis: Chamber Music (London, 1944)

Beethoven (London, 1944)

Musical Articles from the Encyclopedia Britannica (London, 1944)

Essays and Lectures on Music (US: The Main Stream of Music and other Essays) (London, 1949)

The Classics of Music: Talks, Essays, and other Writings previously uncollected, ed. Michael Tilmouth, David Kimbell and Roger Savage (Oxford, 2001)

Secondary Sources

Burnham, Scott. ‘Form.’ The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, Thomas Christensen ed. Cambridge, 2002, pp. 880–906.

Dale, Catherine. Music Analysis in Britain in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. Aldershot, 2003.

Kerman, Joseph. ‘Tovey’s Beethoven.’ Beethoven Studies 2, Alan Tyson ed. London, 1977, pp. 171–91.

Monelle, Raymond. ‘Tovey’s Marginalia.’ The Musical Times 131 (1990), pp. 351–54.

Rosen, Charles. The Classical Style. London, 1971.

Spitzer, Michael. ‘Tovey’s Evolutionary Metaphors.’ Music Analysis 24 (2005), pp. 437–69.

Thorau, Christian. ‘“What Ought to Be Heard”: Touristic Listening and the Guided Ear.’ The Oxford Handbook of Music Listening in the 19th and 20th Centuries, Christian Thorau and Hansjakob Ziemer ed. Oxford, 2019, pp. 207–27.

Webster, James. ‘Schubert’s Sonata Form and Brahms’s First Maturity. 19th-Century Music 2, 3 (1978, 1979), pp. 18–35, 52–71.